Doctors turn to more addictive short-acting benzodiazepines

Dr C Heather Ashton, DM, FRCP, Clinical Psychopharmacology Unit, Medical School, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 4HH, England, DRUGLINK, 1988

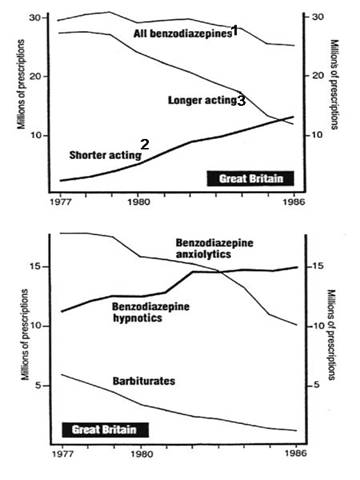

1. Excluding Clonazepam, which is marketed only for treating epilepsy.

2. Includes: temazepam, lorazepam, triazolam, oxazepam, lormetazepam, loprazolam, alprazolam, bromazepam, ketazolam.

3. Includes: nitrazepam, diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, clobazam, flurazepam, clorazepate, flunitrazepam, medazepam, prazepam.

Figures recently released by the DHSS show that prescribing of the type of benzodiazepines thought most likely to lead to withdrawal problems has been increasing, even though the total number of benzodiazepines prescribed is falling. It also appears that while doctors have reacted to bad publicity about benzodiazepine dependence by cutting down on their use for daytime anxiety-relief, the message has not got through that benzodiazepines prescribed as sleeping pills may be just as likely to cause dependence.

The British national formulary – the official prescribing guide issued by the BMA and the Pharmaceutical Society – warns doctors that "Withdrawal phenomena are more common with the short-acting benzodiazepines." The rapid elimination of these drugs from the body causes a relatively steep fall in blood concentrations: the steeper the fall in blood concentrations, the more severe the withdrawal. In contrast, the slower rate of elimination of longer acting benzodiazepines such as diazepam provides a built-in tapering effect that helps minimise withdrawal problems.

Prescribing of shorter-acting benzodiazepines has been increasing over the last 10 years (top figure). In 1977, they represented just over seven per cent of all the benzodiazepines prescribed in Great Britain; by 1986, nearly 53 per cent. Despite the greater risk of withdrawal and dependence, these newer drugs are increasingly used as hypnotics (to promote sleep) because their short duration of action helps prevent residual morning sleepiness (the ‘hangover' effect). Used as anxiolytics (for anxiety-relief), they minimise the extent to which the drug accumulates in the body as fresh doses pile up on the remains of the previous dose.

Must popular of the shorter-acting anxiolytics is: lorazepam (Ativan, etc), now prescribed almost three times as often as chlordiazepoxide (Librium, etc). At 3,149,000 prescriptions in Great Britain in 1986, lorazepam is the second most frequently prescribed anxiolytic. The steep fall in blood levels characteristic of short-acting drugs is aggravated in the case of lorazepam by difficulties in achieving a gradual reduction by taking smaller doses, leading to particularly severe withdrawal problems (see page 14 of this issue of Druglink).

Any benzodiazepine used in lower doses has an anxiety-relieving effect and in higher doses promotes sleep, but differing pharmacological profiles, tradition and marketing have led to the drugs being divided into anxiolytics and hypnotics. Publicity about dependence problems has concentrated on the daytime use of benzodiazepine anxiolytics such as Valium. Between 1977 and 1986, doctors reduced their prescribing of these drugs by over seven and a half million prescriptions. However, prescribing of benzodiazepine hypnotics shows no signs of falling off, having remained stable at 14-15 million prescriptions for the last five years (second figure).

These latest statistics raise queries about the extent to which any reduction in dependence problems associated with the drop in benzodiazepine prescribing may have been counteracted by increasing use of shorter acting compounds. They also suggest that attempts to achieve further major reductions in prescribing will have to tackle the less dramatic but now more widespread use of benzodiazepines as hypnotics. One seemingly unqualified bright spot in recent prescribing trends is the continuing drop in the prescribing of the overdose-prone barbiturates, down to just 1.3 million prescriptions in 1986.